Introduction

I have long been a critic of Land Value Taxes (LVTs) online. This has not been a popular position to take within neoliberal and YIMBY internet circles, but one I think is correct. Over the course of a few blog posts, I will outline my thoughts regarding LVTs. I will expand upon arguments I’ve made on Twitter and reddit over the years, and keep them all in one spot so I can refer people to my larger arguments.

I will make my arguments over a series of blog posts. Specifically, I want to outline the practical problems I see with LVTs and why I think LVTs are a second or even third rate policy option concerning the national housing shortage and affordability crisis. Additionally, I will present my thoughts on how to overcome the practical problems I will outline, and apply my proposed solutions using Philadelphia housing data.

Why should you care?

If you’ve made it this far, you are probably either friends with me and giving me a pity-read, or you are pumped up and ready to hate-read your way through an otherwise boring day at work (you’re definitely not reading this on a weekend). If you are the latter - someone who is Henry George pilled - you might be thinking “Who does this guy think he is - all YIMBYs support LVTs! Everyone knows they’re the best tax!”. I’d merely ask: how do you know? How do you know that LVTs are the best tax? How do you know that they will perform in the real world as well as they do in theory?

Many of us YIMBYs make claims I’m not sure we have the strongest evidence for. By evidence, I mean well identified, peer reviewed papers.

“Of course increasing housing supply decreases housing prices - simple supply and demand analysis confirms this!”

A priori theorizing is useful up to a point, but it is not evidence. We need to provide evidence if we are to be credible to the general public.1 Because I think we should interrogate how we know our claims are true, I’ve asked “how do you know?” of LVT supporters, and I’ve found their answers wanting. I will do my best to represent their arguments, and my criticisms of these arguments.

Setting the stage

In order to cut down on the length of these blog posts, I will assume you have familiarity with most terms. If I feel you don’t know what I mean, I’ll try and explain it as best I can.

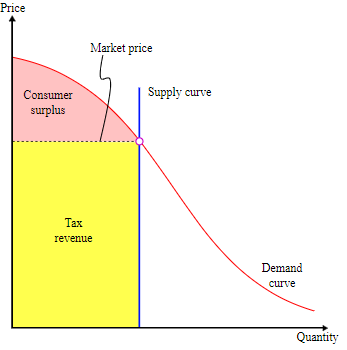

LVTs can be broken into two parts: the effects of the tax and figuring out what land value is (generally, the price of land). We can think about this visually. Everyone knows this graph from the Wikipedia article on LVTs:

Land is of fixed supply, so the supply curve is vertical - perfectly inelastic. Therefore, a tax on it has no deadweight loss, and all tax revenue captures producer surplus. The effects of the tax are really good: the tax is non-distortionary and producer surplus is appropriated. The appropriation is normatively good, as the land owners didn’t actually “produce” anything and would otherwise collect economic rents.

There are secondary effects of the tax, such as encouraging development of the land as land owners cannot make money off of merely holding the land - they must instead put the land to productive use to make money off the land. I will tackle this issue in a future blog post.

The point of this blog post is to focus on the “market price” in the graph above. What is the “market price” of land, the land’s value? Not conceptually - give me a number. Okay, now how do you know that that is the correct number?

Estimating Land Value

My main contention with LVTs is that you can’t accurately estimate land value. This is a bold claim, as many governments currently “calculate” land value when assessing property taxes. But again: how do you know that the assessed land value is correct? How do you know you are not being over- (or under-) taxed?

Land value is essentially unobservable. Yes, we all have the intuition that land value is higher in urban areas than suburban areas, higher in San Francisco than Philadelphia, and higher in Center City Philadelphia than North Philadelphia. But those are relative, not dollar values. For developed property, we can generally decompose property values into:

Property Value = Improvement Value + Land Value + Other Stuff

“Improvement Value” would be the value of the building itself. This would be (roughly) the cashflows derived from the building such as how much rent one can get (or in the case of owner-occupiers, the imputed rent). “Other Stuff” would be idiosyncrasies about the property - perhaps the property is a unique Mid Century Modern home or is a historical building. “Land Value” is the residual.

But all of the things on the right hand side of the equation are unobserved. We only ever observe the price of the developed property if it is sold on the market. Everything else we have to make assumptions about but cannot check to see if we were correct. These values are fundamentally unverifiable..

Consider a business problem: you own a cafe and want to predict how many customers will come in during the week, so you can staff accordingly. You are crafty and use historical data on how many customers come into your store and find a good predictive model. You then use this model to give schedules to your workers. In the following week, you have new data about how many customers have come to your cafe. You can use this new out of sample data to evaluate whether your predictive model was any good.

Now imagine you’re the taxman in your local government. You’ve come up with land value estimates for all the properties in your city. How do you compare these estimates with out of sample data? You can’t - you never directly observe land value.2

“Why is this an issue?”, you might ask. There are costs to over-taxing: if you tax land value in excess of 100%, you will eat into profits of property improvements and discourage productive activity. There’s also evidence that governments systematically discriminate against Black and Hispanic homeowners in property valuations, so we need to verify that governments are treating their citizens equitably.

There are costs to under-taxing. Let’s say you want to fully replace a property tax with an LVT. If you under-tax, you will leave money on the table and starve your government of much-needed tax revenue. If you consistently under-tax land value, you will have to rely on distortionary taxes (such as income taxes, taxes on improvements, or sales taxes) to raise revenue.3

But my point is that, fundamentally, you cannot verify if your land value estimates are correct. This is because we are taxing the price of something that has no market; the government is coming up with a price on its own.

Common Methods for Estimating Land Value

If you are a skeptical reader, you might be thinking to yourself “does this guy know anything about common property valuation methods? There are indeed ways to tease out land value, even with a limited market in land.” In fact, I do know a bit about them! And I’d like to address common methods for imputing land value and why I still think they’re not useful.

Vacant Lots and Teardown Sales

A common suggestion by the pro-LVT group is to use vacant lot sales and teardown sales as estimates for land value. We would expect land value to be the same over some geographic area. By this logic, if a vacant lot is sold in some geographic area then the price of that vacant lot can be used as an estimate of the land value for the entire area. Similarly, a sale of a property which is torn down can be seen as the same as vacant (as the owner is primarily buying the parcel for its land, not its improvement). Once adjusted for the cost of removing the improvement, the residual price is the land value.

This method is fraught. What happens when there are no vacant lot sales or teardown sales nearby?4 As it stands, developed properties don’t turn over very often. In contrast to what many Georgists think, people don’t hold vacant land in high land value areas. Areas with high land value tend to be very developed, areas with low land value tend to be undeveloped.5 Furthermore, if a 100% LVT were in place, there’d be no incentive to have a vacant lot so vacant lots would disappear, meaning we’d have to rely entirely on rare teardown sales.

Additionally, vacant lots might not be comparable. Say a nearby lot zoned for single family housing is purchased by a developer who subsequently submits a variance to build a multifamily unit. The land there is worth more, as it is more productive due to the variance and is not directly comparable to single family homes nearby.

Replacement Costs

An alternative that is applicable to all developed properties is the use of replacement costs to estimate land value. The argument is that the the property prices can be decomposed into two pieces:

Property Price = Land Value + Replacement Cost

If we have an estimate of property prices, we can use an estimate of the replacement cost of the improvement to extract land value. This seems straightforward. What’s the big deal? Firstly, we’re relying on two estimates to create a third estimate: an estimate of property prices (at least for properties that aren’t sold) and an estimate of replacement costs. Are we certain that we are estimating property values and replacement costs correctly? The IAAO is itself skeptical of using replacement cost estimates for properties that aren’t industrial or unique buildings (i.e. churches).

Secondly, the residual of Property Price - Replacement Cost being Land Value should raise some red flags. This accounting identity would imply a very strict zero profit rule for investment properties. We would expect that the price of an investment property is the expected discounted cashflow of its units. Part of the cashflows of the units certainly comes from land rents, but some of the cashflows come from the risk that a landlord takes from being a property owner and manager.6 So we should decompose property prices into:

Property Price = Land Value + Replacement Cost + Risk Premium

The risk premium is - again! - unobserved. By taxing the residual of Property Price - Replacement Cost you are taxing both land value and a risk premium, effectively reducing the incentive to provide landlord services to zero.7

We have to do something!

You may be reading this and think “okay sure, these are fair criticisms, but doesn’t this apply to any Pigouvian tax? Surely you don’t oppose carbon taxes?”. I don’t oppose carbon taxes or other Pigouvian taxes, both of which require an unverifiable estimate of the social cost of the activity.

I will start by stating that I do not feel that there is as big a moral imperative to tax away land-rents as you might think there is. Yes, these rents are unearned but I don’t think they matter all that much in today’s world. Housing is expensive because we don’t build enough - housing is in short supply and housing prices are monopoly rents, not land rents. Wealth today is not a function of how much land you own as economic production is not as tied to land like it was when we were an agrarian society.

By contrast, I think climate change is a huge problem. If we tax carbon too much, I honestly don’t care if it is not socially optimal - it will hurt us all in the short run but it would only hasten the end of producing carbon emissions.

However, I think this criticism of my arguments is the most compelling and for some time, I did not have a good answer besides my argument above: I just don’t think land-rents are a big deal, but I think climate change is a big deal. This is not satisfying to you, nor to me. In the next few blog posts I will present my thinking on how to overcome the difficulties of estimating land value and attempt to apply these solutions on Philadelphia property data.

Conclusion

In this blog post I’ve outlined my central argument against LVTs. I do not think they’re wrong theoretically but rather are incredibly hard to implement in practice due to a calculation problem. There is no market in land, ergo no price for land, and thus we have no way to tax land accurately. The government must set a price for land that it then taxes. There is a deep irony among many right-YIMBYs and neoliberals who support LVTs: they oppose rent control for generally Hayekian reasons but think the government can set prices for land.

There’s a strong counterargument to my claims, which is that I personally support things like carbon taxes despite the same knowledge problem applying to the social cost of carbon. This counterargument is incredibly compelling to me, and one I’ve taken to heart. I believe I have a solution to the land value estimation problem - but this will be a future blog post. I have also not discussed non-tax solutions (such as government run land auctions) which I plan on addressing.

I hope this has been an interesting inaugural blog post for readers and welcome comments and critiques.

To be clear, I think increasing housing supply will decrease or at least stabilize housing prices, for both theoretical reasons and because this is plainly true in Tokyo.

By contrast you can evaluate whether your property values are accurate by comparing the property assessments to the sale of the property - if that happens for the property anyway.

Additionally, if you think land-rents are a social evil like Henry George did, then you’re allowing landowners to retain unearned profits.

Even “nearby” is vague. How does one define where “nearby” starts or ends? Regionalization is a difficult task and still introduces discrete boundaries. I don’t think this task is insurmountable and in fact the City of Philadelphia has created block-level Geographic Market Areas.

“How do you know?” I will cover this in another blog post, I promise!

Indeed this is the social benefit landlords provide: taking on the risk of owning and managing a property so that tenants do not need to.

I’ve outline two pricing equations for property. People who are smarter than me should weigh in, but I think the first equation is roughly the “demand” function and the second equation is roughly the “supply” function.

Your arguments about the impracticality of assessment are a straw-man. LVT can be implemented in practice using Vickrey auctions to price land values and a Harberger tax to price improvements, separately.

Not only does your argument fail to carry the conclusion LVT has a "fundamental problem," you blatantly failed to do any research into the substantial peer-reviewed evidence of the efficacy of LVT in historical practice.

"Land-Value Taxation around the World," Andelson (2000).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3487821

https://www.wiley.com/en-sg/Land+Value+Taxation+Around+the+World:+Studies+in+Economic+Reform+and+Social+Justice,+3rd+Edition-p-9780631226147

"Taxing Land More than Buildings: The Record in Pennsylvania," Cord (1983).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3700954?&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

"A Markov Chain Monte Carlo Analysis of the Effect of Two-Rate Property Taxes on Construction [in Pennsylvania]," Plassmann & Tideman (2000).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S009411909992140X

"The Impact of Urban Land Taxation: The Pittsburgh Experience," Oates & Schwab (1997).

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/NTJ41789240

https://cooperative-individualism.org/oates-wallace_the-impact-of-urban-land-taxation-1997-mar.pdf

"Land Value Taxes and Wilmington, Delaware: A Case Study," Craig (2003).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41954420

"Land value taxation and housing development: Effects of the property tax reform in three types of cities," Bourassa (1990).

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3487525

"Land value taxation and the valuation of land in Australia," Mangioni (2014).

https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/34111

https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/10453/34111/1/nj214_mangioni_v01-1%20Final%20Paper.pdf

"Land Value Taxation in Vancouver: Rent-Seeking and the Tax Revolt," England (2018).

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ajes.12218

Other Academic Literature

Dye & England, "Land Value Taxation: Theory, Evidence, and Practice."

https://www.amazon.com/Land-Value-Taxation-Evidence-Practice/dp/1558441859

Dye & England, "Assessing the Theory and Practice of Land Value Taxation."

https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/assessing-theory-practice-land-value-taxation-full_0.pdf

Haughwout, "Land taxation in New York City: a general equilibrium analysis."

https://www.elgaronline.com/display/1843763818.00011.xml

Hirsch, "Land Values Taxation In Practice."

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89097112049&view=1up&seq=10

Lent, "The Taxation of Land Value."

https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/024/1967/001/article-A004-en.xml?ArticleTabs=abstract

Your arguments are sound to be careful not over-valuing land, but to me you did not provide an argument against under-valuation. Sure, we'll have to resort to distortionary taxes, but we already do, and we won't have to resort to them as much as now.

Also, I don't see the goal of LVT as solving the housing crisis. For me their goal is just to fund public goods (in a non-distortionary wat).

I am not at all a specialist but I'd tend to estimate land value by subtracting the property values at different locations with similar improvements. To be precise, this would estimate the difference in land values between locations. Then you arbitrarily set to 0 the land value of the cheapest location. This convention helps to not overvalue land.

Finally, I don't think the parallel with the carbon tax is a good argument against yours. Because the uncertainty on the optimal carbon tax does not call not to tax, but to prudently choose the tax level. You claim to argue that both under- and overtaxing land would be bad, so it's not a question of imprecise level for you, but of taxing at all. (If it were a question of imprecise level, you could implement a LVT at the lower bound of plausible land value; and we're back to my second point: I don't get why you oppose this.)